The King of Central Park West

"The highest-priced new apartment building in the history of New

York—indeed, at roughly $2 billion in sales, the most lucrative in the

world—isn’t a sleek, one-of-a-kind glass tower. It’s architect

Robert A.

M. Stern’s 15 Central Park West,

an ingenious homage to the classic Candela-designed [Rosario

Candela not

Félix Candela -RDP] apartment buildings on Park and Fifth Avenues

where apartments have been snapped up by hotshot hedge-fund managers,

established financial titans, and celebrities such as Sting, Denzel

Washington, and Bob Costas. From the marble-columned lobby to the wine

cellar and pool, the author examines the art, as well as the limits, of

Stern’s grand nostalgia.

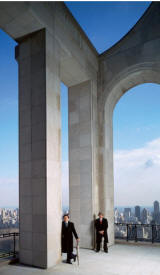

During the frenetic building spree of the last decade, when architects

and developers seemed willing to try just about anything to get their

projects noticed in the hyperactive Manhattan luxury-condominium market,

buildings tended to fall into two categories: either they were based on

the premise that an architect’s job is to invent something that you have

never seen before, or they were not. Most of the buildings that have

gotten attention lately have been in the first category, sleek glass

condominiums by the likes of

Richard Meier,

Jean Nouvel,

Charles Gwathmey, and

Herzog and de

Meuron that nobody could mistake for anything but new, one-of-a-kind

creations, the sorts of places where apartments sold for unbelievable

amounts of money to people who live in them maybe a few weeks out of

every year. There have been round towers, square towers, blue towers,

and green ones, not to mention towers that swirl and towers that look as

if they were disintegrating, each of them known as much by its

architect’s name as by its address. And then, as if inspired by the work

of these celebrity architects, a whole other group of real-estate

developers, the kind who like to refer to buildings as “product,”

started turning out their own glass apartment towers, much more mundane

but in such quantity that you could easily think that glass, which once

signified an office building, had now become the material of choice for

luxury apartment living in New York.

As all of that was happening, the developers

Arthur and William Lie Zeckendorf hired

Robert A. M. Stern, who told them that what he thought

New York really needed was a luxury building that looked more like the

old-fashioned ones, not less.

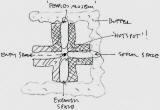

Stern has made a career out of paying homage to the city’s architecture

of the 20s and 30s; he knows the classic buildings as well as most

real-estate brokers. He sees himself, he has said, as a portraitist, as

an artist whose work comes from putting his own gloss on what he sees in

front of him, not from creating out of whole cloth.

The apartments were sold out before construction was completed this

year, at the highest prices of any new building in the history of New

York. The Zeckendorfs started selling them at roughly $2,500 a square

foot, which was already at the top of the New York market, and they kept

raising the prices as construction went on, until the last apartments

were sold at something approaching $4,000 a square foot." |

|